- Details

- Written by Philip Kerpen

- Hits: 2417

- Information

- 7 mn read - Subscribe

How to Protect your AI Innovations with a Patent: Updated EPO Guidelines

- Information

- First published 19 October 2019 - co-author(s): Dany Vogel

Software has become ubiquitous: it has reached almost all areas of industry and commerce. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in particular are game-changers – fueled by more data and faster hardware they show no signs of slowing down. Ever increasingly it is the software component of products and services which plays the decisive role in determining their success. In fact, a strong integration of software into your products can end up changing your business model.

The purpose of this blog post is to go through the part of the updated Guidelines of the European Patent Office (EPO) which relate to artificial intelligence and machine learning. The updated Guidelines will come into effect on the 1 November 2019 and they will be used by the EPO during the examination of patent applications. It is also our aim to bring across the basics of patenting AI inventions with some practical tips and strategies.

"The New Electricity"

"Just as electricity transformed almost everything 100 years ago, today I actually have a hard time thinking of an industry that I don’t think AI will transform in the next several years," – Andrew Ng, one of the foremost experts on AI.

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are here to stay. Besting humans in complex games such as Go and Poker was just the beginning. Today, companies in fields as diverse as life and medical sciences, telecommunications, energy management, security, and manufacturing are seeing the benefits that artificial intelligence and machine learning can bring. This impact is reflected both in the number of scientific publications in the field (over 1.6 million and counting) and also in the number of patent filings (nearly 340'000 worldwide to date). The pace shows no signs of slowing down: patent filings in deep learning (an area of AI) experienced an average annual growth rate of 175% between 2013 and 2016. Computer vision, biometrics, natural language and speech processing, robotics, and predictive analytics are some of the technological areas which have seen the largest number of patent filings. WIPO Technology Trends 2019: Artificial Intelligence

Is AI not an unpatentable abstract mathematical idea?

The abstract mathematical nature of the computational methods and algorithms behind artificial intelligence and machine learning does not preclude them from patentability in Europe altogether. Although the computational methods and the algorithms taken by themselves are abstract mathematical ideas and therefore cannot be patented according to European patent law, technical solutions to technical problems are patentable. Therefore, if the AI component (e.g. a neural network) of an invention is directed towards achieving a technical effect, it can make a technical contribution and make the patent allowable.

In light of this, the EPO has specifically mentioned artificial intelligence and machine learning in their updated guidelines for examination of patent applications. The updated guidelines confirm that the EPO is treating artificial intelligence and machine learning in line with the settled case law and general practice of the EPO regarding software patents, which is permissive to patents on software directed towards achieving a technical effect.

What needs to be considered when assessing an AI invention?

To help clarify whether the AI technology your company has developed may be susceptible to patentability, we recommend asking: what does the AI do or enable? It may be that the AI component is able to make sense of data in a novel way, for example finding previously hidden correlations and relationships, or it may be that the AI component provides better robustness or accuracy than previous methods. It may also be that the AI component increases the speed of a calculation and therefore achieves computational efficiency, or that it allows a calculation to be carried out on a piece of low-power hardware such as an IoT device or a smartphone.

It is also important to understand what kind of data is used and produced by the AI: what data is input into the AI and what is the data output? If the input data is of a technical nature, such as physical quantities (i.e. measurable by a device, such as temperature, noise, position), then it is more likely that the AI-component makes a technical contribution and the invention could be susceptible to patentability. Likewise, if the output of the AI-component is used to achieve a technical effect beyond the normal interaction that occurs between software and the processor, then chances are good that the invention could be patentable. If neither of these is the case, then the invention needs to be looked at more closely, as it is often the subtleties of a particular invention that become decisive.

How does this work in practice?

In this section, we provide more patent specific details and recommendations regarding European patent practice.

In general, an AI invention can be placed in one of the following three categories:

- AI algorithms as such: these are currently not patentable as they are not considered inventions under Art. 52 EPC. For example, this could apply when a patent is sought for an AI algorithm on its own - separate from any technical context.

- Generic trained models: a generic trained model which can be applied to many technical problems may be difficult to patent – providing sufficient comparative examples and parameter ranges may be needed. For example, if an AI invention is capable of both detecting anomalies in MRI images and determining the wear of truck tires, we would recommend providing sufficient detail for both cases – or filing separate patent applications, each directed to one particular technical problem (and application).

- AI applied to a particular technical problem – here the AI component is typically part of an encompassing claim which is directed towards a concrete technical problem, and therefore is patent eligible.

Read the whole EPO Conference Summary: Patenting Artificial Intelligence.

When filing AI patent applications, we recommend including in the specification as much information as possible regarding the technical effect produced or enabled by the AI component. Further, defining the AI component (e.g. by specifying its data input/output and network architecture) is recommended for purposes of sufficient disclosure and clarity. Jargon should be avoided, for example even if a new type of neural network or layer has a name that has been established in a number of scientific publications, it is advantageous to define exactly what is meant.

The claims of the patent application define the subject-matter for which protection is sought. Broad claim types include method and device. For AI inventions we recommend claiming both the method itself, as carried out by a computerised device (defining a step-by-step process of how the invention is carried out), as well as the computerised device itself, configured to implement the method. Further, the steps of generating the training set and training the AI component may also contribute to the technical character and can also be claimed.

How do I protect my AI invention worldwide?

The realities of a globalised world demand that patent protection is sought in multiple countries, depending on which your most important markets are and where your competitors are located. As different national patent offices have slightly different criteria when assessing patent applications, it is vital to select the right national patent office for filing your first application. A good option here is the EPO, as applications which satisfy the European requirements are usually unproblematic when it comes to subsequent filings, for example in the US. In our experience, the converse is not always the case as the US drafting style, in particular regarding software inventions, can lead to objections when it comes to a subsequent European filing.

Within one year of filing the first application, subsequent applications can be filed in other jurisdictions for the same invention. If the number of jurisdictions sought is high, it can make sense to file an international PCT application (Patent Cooperation Treaty), which also has the advantage of giving the applicant another 18 months to decide in which jurisdictions to ultimately file subsequent applications.

Conclusion

The EPO has recognised the importance of artificial intelligence and machine learning in inventions and its updated guidelines underscore that inventions based on artificial intelligence and machine learning will be examined in the manner established for other software inventions. If your company uses, or intends to use, AI in its products or services, we suggest assessing how to best protect and generate value from this intellectual property.

- Details

- Written by Matthias Städeli

- Hits: 2388

- Information

- 4 mn read - Subscribe

Introduction of the Patent Box in Switzerland

- Information

- First published 20 May 2019 - co-author(s): Alfred Köpf

On 19 May 2019, the Swiss electorate voted in favour of implementing the Swiss patent box. Tax advantages on income generated from intellectual property rights will become a valuable tool for companies in Switzerland to promote research and development activities and to generate added value in these areas.

In future, the Swiss patent box will make it possible to tax part of the profits from inventions at a reduced rate. Additionally, cantons will have the option of providing an additional deduction of up to 50% of R&D expenditure.

Which companies benefit from the Swiss patent box?

All companies that conduct research and development in Switzerland and generate patentable technology may benefit from the patent box. The legal ownership of a patent is not important, the decisive factor is the economic ownership (i.e. who has borne the costs of the innovation).

Which IP rights qualify for the Swiss patent box?

Under the new Swiss law, the following IP rights are eligible for the patent box:

- Swiss and foreign patents

- Comparable Swiss and foreign rights as supplementary protection certificates, topographies, plant varieties, as well as documents protected under therapeutic products law and designations protected under agricultural law

Product patents as well as method patents qualify for the patent box.

What is your next step?

It is worthwhile for all companies with scientific and technological developments to review their patent strategy from an intellectual property and tax point of view, allowing them to benefit from the advantages of the patent box. An optimal tax advantage is achieved by a combination of competences in tax and patent law.

For further questions, please contact patent box experts Matthias Städeli or Alfred Köpf, RENTSCH PARTNER.

- Details

- Written by Gregor Wild

- Hits: 1738

- Information

- 6 mn read - Subscribe

Trademark Protection for Blockchain?

- Information

- First published 22 May 2018

It lies in the nature of the blockchain technology that the control and securing of blockchain transactions have a non-proprietary character. The decentralisation of the system shall furthermore guarantee the stability and consistency of this decentralised trust “sphere”. Starting with this characterisation, it seems at first sight to be paradox to openly think about the question, whether trademark rights could play a valuable role in the “blockchain community".

However, as commonly used terms, such as “software”, “Internet”, “social media” or “crowd funding” and the like, generically describe specific methods, technologies or systems, they are public domain and thus free for anyone, without the possibility of monopolisation through trademarks.

This said, we have to distinguish between the term (“trademark”) for a technology or method being public domain, on the one hand, and specific products or services that are developed based on this technology or method, on the other hand. But we must also be aware of the fact that there is a space between technology or method per se and the final product. As many Internet services and applications, e.g. search engines, social media platforms or media streaming, rely on specific (standardised) protocol layers, applications and cryptographic solutions have been developed likewise on the basis of existing blockchain technologies and platforms. Keeping in mind that trademark rights provide an instrument for legal protection of investment, there is no reason why a developer and creator of a specific blockchain solution should be forced to tolerate that a third party is using the same or a confusingly similar name (trademark) for its product. If this would be the case, the third party could profit from the quality reputation and goodwill built and established by the “first mover”. At first sight it is obvious that trademark protection can be obtained for blockchain based products (goods or services) by opting for the accurate class within the Nice classification system – for example: software (class 9), data compilation (class 35), financial transactions (class 36), design and development of a new technology for others (class 42), software as a service (SaaS) (class 42) or licensing of technology (class 45).

Nevertheless, we may also think about alternative options for trademark protection for blockchain brands which are more agreeable with the “open access”-spirit of the blockchain community. Given that the trademark owner wants to have his technology and brand used by as many users as possible, it could make sense to revitalise the institute of a guarantee mark (certification mark or label). Likewise, such certification mark could ensure the protection of a label for standards describing the functions and events that a token contract has to implement (eg. ERC20). A certification mark is used by several users under the supervision of the proprietor of the mark, which serves to guarantee characteristics common to goods or services provided by such users. As a specific trademark type the guarantee mark is acknowledged by the European and the Swiss Legislation (Art. 83 EU Trademark Regulation and Art. 21 Swiss Trademark Act).

We believe that registration and protection of a guarantee mark (label) would combine the interest in a wide market penetration of a technology, on the one hand, with the interest in a good and fair control of reputation and goodwill of blockchain driven products, on the other hand.

- Details

- Written by Demian Stauber

- Hits: 1637

- Information

- 10 mn read - Subscribe

Spotlight on Copyright Issues of Blockchain Technology

- Information

- First published 21 September 2017

With the growing universe of blockchain based systems and applications, legal questions associated with this technology emerge and require consideration (ideally) before substantial sums are invested. In this blog series related to blockchain, we have covered a number of legal aspects (such as Starting an Initial Token Offering (ITO, also called Initial Coin Offering or ICO) - Things to consider and Blockchain for Patents - Patents for Blockchain) already.

This blogpost is about copyright in the blockchain environment.

Traditionally, copyright protects works of authorship, such as literary or musical works, from unauthorised reproduction (copying, alteration etc.).

Now how is this possibly relevant in the context of blockchains? The answer is: software code.

Many countries’ copyright laws protect software code (source and object code) against unauthorised reproduction or alteration. This and possible patents are the reason why you have to accept a license agreement any time you install an app on your mobile phone or a new software on your computer. By this license, the copyright owner grants you the right to use the software in a way that would otherwise be prohibited by copyright law (e.g. installing the software amounts to copying).

Technical and Legal Considerations

Since blockchains (distributed ledgers) and related applications come in a wide variety of implementations, we will only address a few main principles here. Different "pieces" of software can be identified such as

- the blockchain software (implementing the blockchain, such as Bitcoin or Ethereum core)

- Middleware

- Applications integrating with / using the blockchain

- Smart contracts deployed on a blockchain

Since it is the very purpose of blockchains to be computed on a network of different computers, copying the core and all code contained in the blockchain is system-immanent. Moreover, many blockchain projects live from contributions by "the community". Now, what rules govern the use, alteration or copying of such software?

Most public known blockchain projects are open source projects. Open source means that software is licensed under distribution terms that comply with certain criteria (such as access to source code, free redistribution, permission to make modifications and derivative works, no discrimination rules etc., see e.g. the widely used Open Source Definition of the Open Source Initiative).

There is a large number of different open source licenses with significantly different terms (some prominent licenses used for blockchain projects are GNU General Public License, GNU Lesser General Public License [LGPL], Apache License 2.0, MIT license). These licenses impact the way of how the software proliferated under the license may be used, modified and redistributed. Particular attention needs to be paid to the redistribution rights and obligations because several open source licenses require that software or at least the derivative part of the software incorporating the open source software is redistributed again under the same open source terms (“copy-left”, GNU and LGPL).

An example of a basic conflict is reported in an article on the website of ETH News. In essence, Hyperledger "considered hosting projects that would be designed to connect to the ETH chain as a client or be built on top of the Ethereum platform. They attempted to solidify this collaboration by incorporating Ethereum C++ (cpp-ethereum) into Hyperledger but to do so, the C++ iteration would first have to be relicensed before being absorbed." The main reason for this incompatibility was different open source licenses with conflicting terms: Ethereum C++ was licensed under GPL-3, while Hyperledger uses Apache 2.0, which would have required a relicensing of the Ethereum C++ client to the Apache 2.0 license.

The example above also demonstrates that changing a license to another license may become burdensome if not impossible, since this requires consent of the contributors and the number of contributors to blockchain projects can be significant (and contributions can be made under an alias; see the article in the International Business Times).

Surprisingly, though, finding easily accessible and reliable information (other than in the code) about the licensing terms of prominent blockchain projects is a rather cumbersome task. However, it is key to make a proper investigation before starting an own project to avoid unpleasant surprises.

- Details

- Written by Dany Vogel

- Hits: 2319

- Information

- 5 mn read - Subscribe

Blockchain for Patents - Patents for Blockchain

- Information

- First published 12 September 2017

Much has been written and discussed about how blockchain technology would bring about fundamental changes to the financial industry which could actually threaten the very existence of banks as intermediary trust centers. At the latest after the major central banks met about a year ago in Washington at a three-day event, hosted by the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the US Federal Reserve, to discuss blockchain and crypto currencies, it probably dawned on a wider public that the hype around blockchain must be more than just that.

In a recent in-depth analysis report, the European Parliamentary Research Service investigated how blockchain technology could change our lives. Indeed, blockchain has potential for application way beyond Fintech - so the current hype may actually be understated.

Blockchain for Patents

While the Internet provides a global network for sharing and communicating information, blockchain will use this network for managing and transferring value and assets in a distributed trust system. The European Parliament's in-house research department and think tank identified digital contents and rights management, the electoral system, supply chains, and smart contracts as fields of blockchain applications beyond the current crypto currency developments. What is of interest here is that, aside from its potential impact on public services in general, the report pointed out that blockchain could help the patent system. While it has been suggested that blockchain could substitute or even abolish the patent system, the report acknowledged that blockchain makes it possible for an innovator to record content, such as a description of an invention, and to proof later the time of recording and the content recorded, without having to reveal the content in the meantime. The report agreed that blockchain could reduce inefficiencies in the registration process across several national patent systems, but found that blockchain did not lend itself to promoting innovation, as it does not provide for publication and cannot assess novelty and other patentability requirements, as patent examiners do. Nevertheless, as the number of patent applications continues to increase, so will the demand for a more efficient patent system. In a system where novelty and inventive step of patent applications are examined only per request and as needed, blockchain could very well be the basis for a global registration system for innovation. The addition of an automatic and verifiable content publishing system and an automatic payment system for filing and annuity fees would be relatively straightforward. At least from a technical perspective, blockchain must be considered an efficient alternative or addition to the present patent system.

Patents for Blockchain

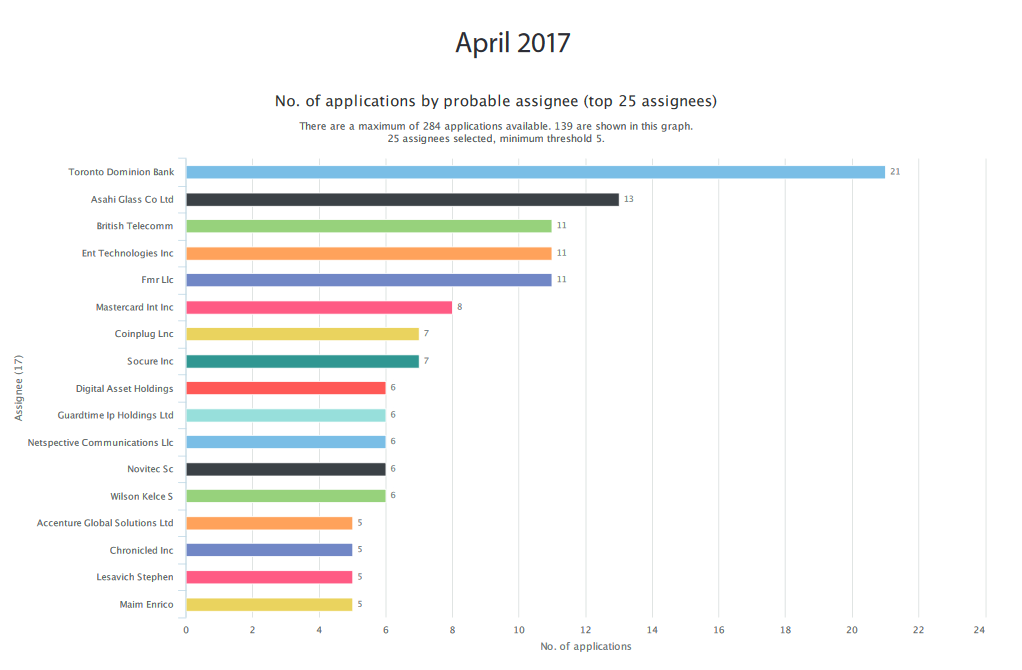

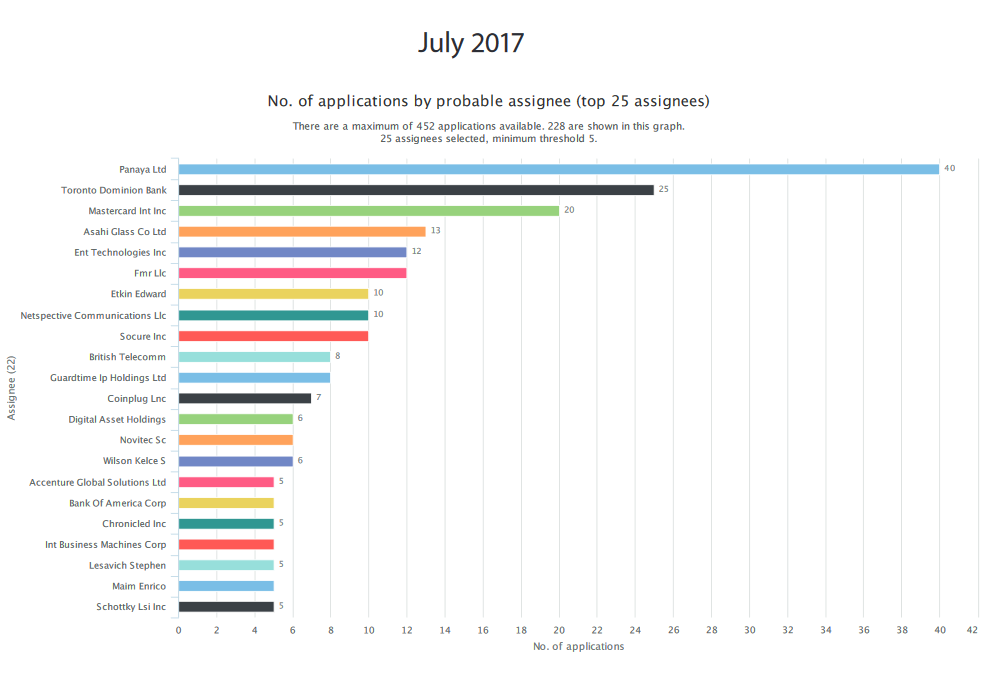

The application of blockchain is and will not be limited to the financial and legal sectors. With the advent of Internet of Things and cloud-based data processing and their propagation to virtually all kinds of technologies and industries comes a need for logging and registering events and values with critical requirements of reliability, security, and verifiability, qualities which are inherent to blockchain. The application of blockchain in technical fields will spur innovation and with it patent applications. The current numbers of published patent applications related to blockchain are still low, worldwide in the range of about two hundred patent families, primarily from the financial sector. Although there is a blind spot of a year and a half, because patent applications are published as late as eighteen months after their filing, it is evident that the numbers are growing rapidly. In just the last three months, the number of published US patent applications increased from 123 to 225. Worldwide, this rapid growth is indicated by an increase of patent families from 175 to 250, with published patent applications growing from 284 to 425 in the same short period. This tremendous activity is further evidenced by the appearance of new applicants, with top ranking numbers of applications, and a broadening of relevant fields from finances to information and communications technology.

But can blockchain related innovations be patented and is it worth it? In general, at the onset of new technological fields, the claims can be staked broader than in mature fields, where innovation is typically directed to small improvements. So yes, in that sense it could very well be worth it.

But what can be patented? In essence, blockchain related innovations are software inventions and the same rules apply, i.e. the same laws and case law, as for any other computer-implemented inventions. The European Patent Office, for example, requires that a claimed invention provide a solution to a technical problem in order to be patentable. According to the case law in the United States, a claimed invention is only eligible to a patent, if it is directed to significantly more than an abstract idea. Provided it is new and non-obvious, a specific technical application of blockchain will be amenable to patent protection in most jurisdictions.

Page 5 of 5